REVIEW: SALÓN FLAMENCO by Lillian Jean Shaddick

Reflections on Salón Flamenco 2023 by Lillian Jean Shaddick.

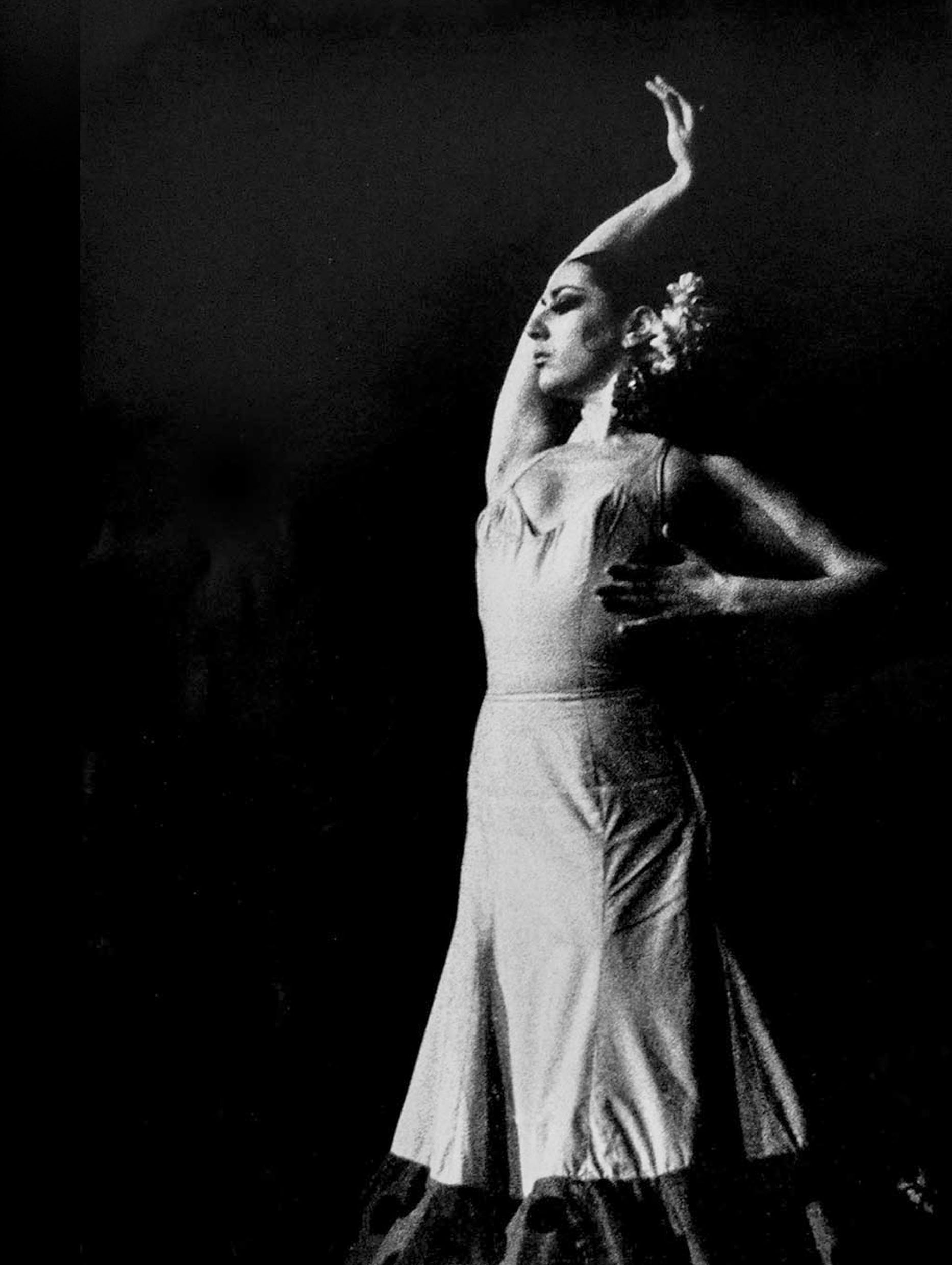

The 2023 Salón Flamenco performances opened with a short dance film, Al Verla Muerta, (Seeing Her Dead) by Lisa Maris McDonell. The title of the piece named after the music that accompanied it by Niño de Elche, a flamenco artist who is well known for pushing against the traditional and delving into difference with his singing and musical composition. The shots were sucked of colour and cut to show varying angles of McDonell as she dances independently, twisting and extending her body, kicking up the dust of the Plaza de Toros in Ronda: a fitting location as a place of death and display.

Lisa Maris McDonell in Al Verla Muerta, a dance film. Photography courtesy of the artist.

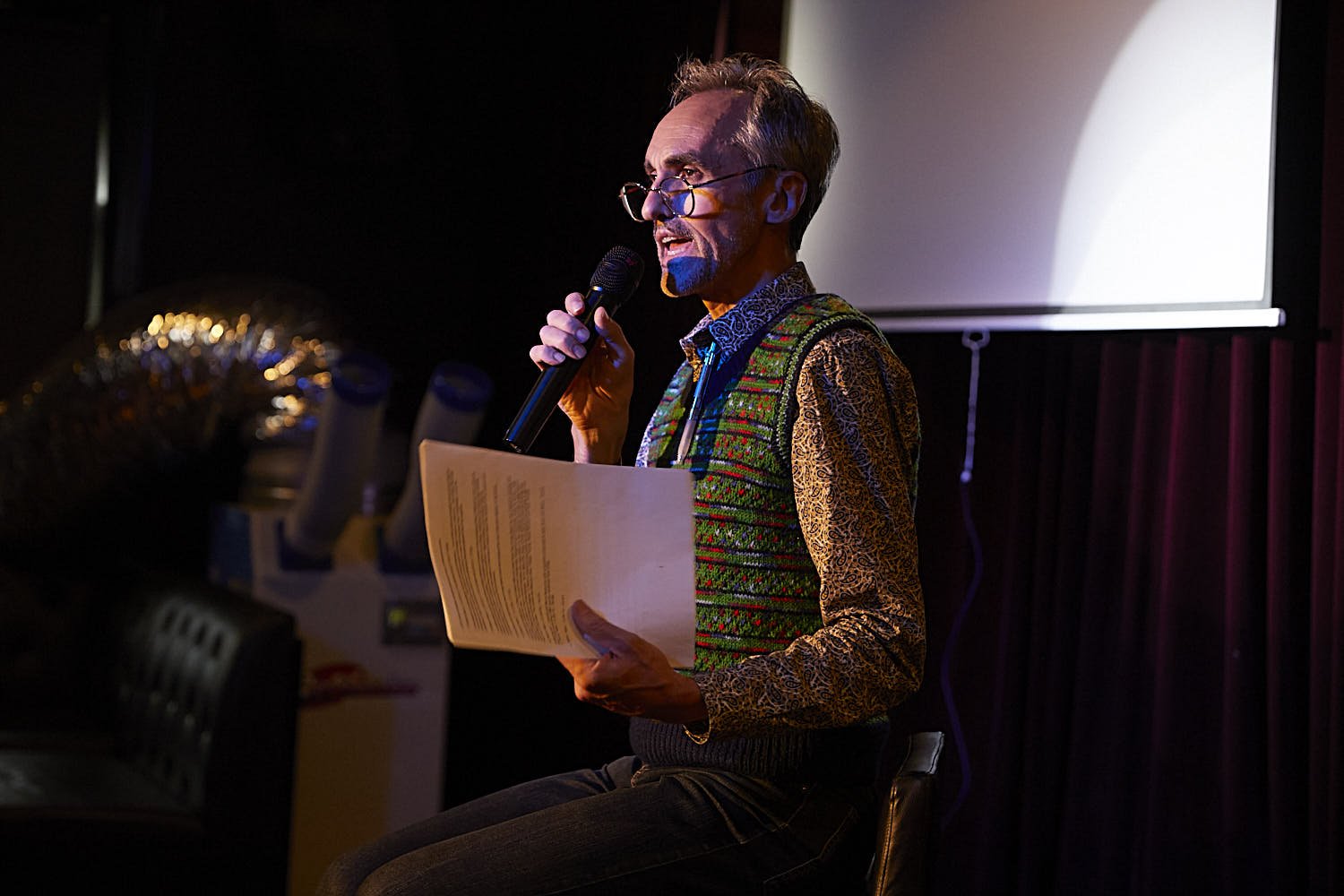

Marduk Gault’s improvised guitar performance involved a visual technical setup not commonly seen in flamenco performance. Even when performances use complicated microphone systems, they are usually hidden from audiences so as to not break the illusion of a predominantly acoustic display. Rather, Gault embraced his table banquet of tech, and as he attached a wire extending from his set up to his guitar he stated, “My guitar maker would kill me if he saw me doing this”. We laughed nervously, still unsure of what he was about to do. As he began to play with the distorted echo sounds washing over each chord, we searched for that distinctive flamenco cadence. Ahh, there it is, a faint but distinctive chord progression that the room full of flamenco aficionados (enthusiasts) would hear a mile away.

Marduk Gault. Photography by Shane Rozario

Paloma Negra and Benedict Leslie performed two pieces, the first whirling bright, almost neon, coloured scarves that were a welcome nod to Pride week and the second, a sevillanas, the highlight being when Leslie utilised a pole near the stage to twirl around receiving a large whoop from the audience.

Below: Paloma Negra and Benedict Leslie in performance. Photography by Paula Ninkovic and Shane Rozario.

Rodolfa Biasotto performed a more traditional flamenco dance accompanied by Marduk Gault. Farruca, a nice reminder of how far flamenco has come in modernisation through the normalisation of a dance that was at one point only performed by men.

Rodolfa Biasotto performing a Farruca. Photography by Paula Ninkovic.

Tomás Arroquero, the final performer of the night, began by weaving through the audience in his black and white polka dot bath robe. He made several on-stage costume changes – a long black flamenco skirt, a Madonna print t-shirt and shiny white sports shorts, to almost wearing a traditional blue a white flamenco polka-dot dress. I couldn’t help but think of this as a metaphor for the negotiations queer performers make with their desires for expression and their visual identities in daily life and for audiences. An audio recording of a discussion of the meaning and experience of people with what was described as a ‘gay voice’ played while Arroquero sat on a chair moving to his own elaborate rhythms. The complexity and energy of the sound and spectacle meant you couldn’t relax as you listened to the recording. Near the end of the performance a cute but menacing puppet-like handkerchief, controlled by Arroquero and cut from the same traditional material of the blue and white polka dot dress, smothered him.

Below: Tomás Arroquero in performance. Photography by Paula Ninkovic and Shane Rozario.

On the first day of panel talks titled ‘Queerness in Flamenco’, Arroquero, a flamenco scholar as well as artist, discussed many ideas that seemed to emerge in his performance through his presentation on queerness within flamenco. He focused on the extent to which gatekeeping of the traditional aspects of flamenco practice tend to align with very binary distinctions of gender. This means if you present as a male, you are expected to dance and dress the way a male flamenco dancer traditionally has. For Ryan Rockmore, a flamenco scholar and artist in the United States who Arroquero interviewed, he expressed that wearing the bata de cola, a long flamenco skirt that is very much emblematic of the image of a female flamenco dancer, challenges this binary and these traditional views within flamenco communities. Arroquero’s personal experience in the flamenco world also revealed how even when being an exceptional dancer with cultural, ancestral ties to Spain, one can still feel not ‘flamenco’ or ‘Spanish’ enough due to how certain signifiers of authenticity (often surrounding gender conformity) legitimise one’s place and identity in the practice. His conversation with Belén Maya, a world renown flamenco dancer reinforced this idea, as someone of her calibre with Gitano (Spanish Gypsy/Romani) ancestry can still feel the pressure of living up to or performing according to traditional flamenco values.

L to R: Tomás Arroquerro, Lisa Maris McDonell, Ryan Rockmore, Belén Maya. Photographs by Paula Ninkovic and Shane Rozario and courtesy of the artists.

For the second panel day ‘Flamenco Down Under’ a short documentary film by Alessandra Pecci was shared called “Ser Flamenco” más allá de la patria: self-narratives from Australia. Pecci interviewed flamenco teachers and artists across Australia regarding their experience of and engagement with heritage and tradition through their practice in Australia. These interviews, as Pecci intended, gave not only viewers insight into the ways in which these practitioners negotiate ideas of authenticity but also offered an opportunity for the practitioners themselves to self-reflect, occasionally revealing contradictions and conflict within their own dealings with the looming expectations of ‘respecting tradition’.

“Flamenco Deteritorialsed” a documentary film by Alessandra Pecci. Top: Tomas Dietz, Roshanne Wijeyeratne. Bottom: Annalouise Paul, Damian Wright. Image courtesy of the artists.

Annalouise Paul, a flamenco artist as well as the curator and producer of Salón Flamenco, shared a short documentary of interviews she conducted with ‘Australia’s Flamenco Pioneers’ (as titled). These interviews offered a glimpse into the perhaps differing perspectives of some of Australia’s first flamenco teachers and artists. What struck me the most was the reminder of just how much the sharing and accessibility of flamenco culture and technique has completely transformed.

L to R: Deanna Blacher, Veronica Vargas and El Tití, Juan and Carmen Maravillas, Veronica Gilmer. Photographs courtesy of the artists.

During the panels there was facilitated conversation with the audience who were predominantly made up of other flamenco artists and aficionados. Here, a range of perspectives emerged and evidence of the ongoing contentious debates surrounding taste and authenticity in flamenco being well and truly alive. Contemporary flamenco practitioners admitted that despite the perhaps unhealthy and discriminatory aspects of more traditional flamenco practice, they could not help but still appreciate this style. Equally another audience member who having attended the recent Sara Baras performance (a contemporary, but not particularly controversially so, Spanish flamenco artist) and found it boring, calling it ‘cruise ship’ flamenco, and instead hailed the more ‘street’ or ‘older’ (read traditional) approaches to flamenco.

Below: Nuria Rodriguez Riestra, Paloma Negra and Marduk Gault, Lillian Jean Shaddick and Fleur Denny, Annalouise Paul and Tim. Photography by Paula Ninkovic.

By the end of two days of discussions and performances I felt the negotiations that artists were constantly having to make regarding their authenticity or upkeep of tradition would never cease to be. But there seemed to be a reoccurring theme of what at the very minimal you needed to maintain to be seen as doing flamenco: maintenance of compás. Being able to hold both sonically and visually a rhythm that is recognisable as flamenco was fundamental to not only having one’s performance considered flamenco but also the extent to which one successfully does this, garners them the cultural and social respect to break traditions. Compás refers to the rhythm, cadence, measure, and timing of a piece of music. In the documentary Cante y Compás (documental flamenco filmado en Sevilla y Jerez) there is a quote framed at the Peña Flamenca Los Cernícalos in Jerez de la Frontera, “Fight for the compás and you will have freedom”. Compás in flamenco is the rule that enables you to break rules. This tension in flamenco was explored in the presentations, conversations, and performances. Much of the discussion pointed to flamenco being a practice that is both liberating and creative but equally deeply traditional and strict. The kind of technical and musical competence in simply maintaining and contributing to compás almost signals to audiences, “I know what I’m doing, I have done the hours, now listen to what I have to say”. As Arroquero smashed out an explosive remate in his performance, he captured his audience’s attention to then share with them themes that challenged societal views on gender and sexuality.

Salón Flamenco audience at Stonewall Hotel with Marduk Gault on stage. Photography Shane Rozario

As a performance studies scholar, about to submit a PhD thesis on the embodied experience of flamenco at the University of Sydney, I commend Annalouise Paul for bringing together this small yet passionate community of flamenco practitioners and enthusiasts to both challenge and be challenged in their perceptions and appreciations of flamenco. I had to pinch myself at how lucky I was to be able to attend this niche yet widely relevant artistic and academic conversation to many cross-cultural arts practices in Australia.

Lillian Jean Shaddick April 10, 2023